To read the full report click

Appendix A

Appendix A

Letters patent

Appendix B

Appendix B

Amended letters patent

Appendix C

Appendix C

Further amended letters patent

Appendix D

Appendix D

Acknowledgements

Many people provided invaluable support to the work of the Commission. Their effort should be acknowledged.

Mr Adrian Finanzio, SC, Ms Penny Neskovcin, QC, Ms Meg O’Sullivan and Mr Geoffrey Kozminsky worked tirelessly throughout the course of the inquiry in their role as assisting counsel.

They were ably instructed by a dedicated team of lawyers from Corrs Chambers Westgarth led by Ms Abigail Gill and Mr Craig Phillips.

Particular mention should be made of the assistance given to the Commission by Ms Elizabeth Langdon in her role as Chief Executive Officer. Without her assistance the Commission could not have run as smoothly as it did.

My personal assistant, Ms Victoria Wilson, was as usual dedicated in her work. My associate, Ms Lillian Vadasz, always provided me with frank and helpful advice.

I also wish to acknowledge collectively the assistance of the following people:

Office of the Chief Executive Officer

Andrew Thackrah

Laura Missingham

Charlotte Walker

Barristers

Tim Jeffrie

John Maloney

Stephanie Hooper

Ella Delany

Jacqui Fumberger

Policy and Research

Dahni Houseman

James Lavery

Joanne Motbey

Alicia Robson

Anusha Kenny

Rochelle Rasiah

Investigations

Michael Stefanovic, AM

Stuart Macintyre

Roland Singor

Lindsay Attrill

Media and Communications

Amber Brodecky

Operations

Oliver Way

Marlyn Assad

Nelvis Ribeiro

Legal

Jared Heath

Kate Gill-Herdman

Norah Wright

Andrew Hanna

Emily Steiner

Henry Hall

Isobel Farquharson

Shanee Goldstein

Sophie Uhlhorn

Michelle Chay

Allen Clayton-Greene

Alex Ji

Victoria Phillips

Amanda Liu

Camryn Cooper

James Richards

Alice Maxwell

Kate Mani

Nicholas Garbas

Sonya Marsden

Mel Hayes

Noah Grubb

Bella Green

Amy Catanzariti

Eleanor Clifford

Georgia Whitten

Kevin Sebastian

Matthew D’Angelo

Maxim Oppy

Quynh Trang McGrath

Rebecca Maher

Tamara Ernest

Weng Yi Wong

Zoe Burchill

Legal Technology Solutions: Project Management

Maureen Duffy

Alex Thompson

Alyssa Zambelis

Jordan Morais

Helly Soni

Katie Saliba

Lillie Murdoch

Madeline Pittle

Legal Technology Solutions: Technical Management

Tri Huynh

Dennis Au

Jayani Gunasekera

Iris Le

David Le

Phil Magness

Service providers

Caraniche at Work

Complete Office Supplies P/L

Corrs Chambers Westgarth

ERM International Pty Ltd

Fair Work Commission

Graham Bradley, AM

JA

Kapish (part of the Citadel Group)

Law in Order

Murray Waldren Consulting

Notwithoutrisk Consulting

Proximity

Southern Impact

Spectrum Gaming Group

The Information Access Group

WOO Agency

Appendix E

Appendix E

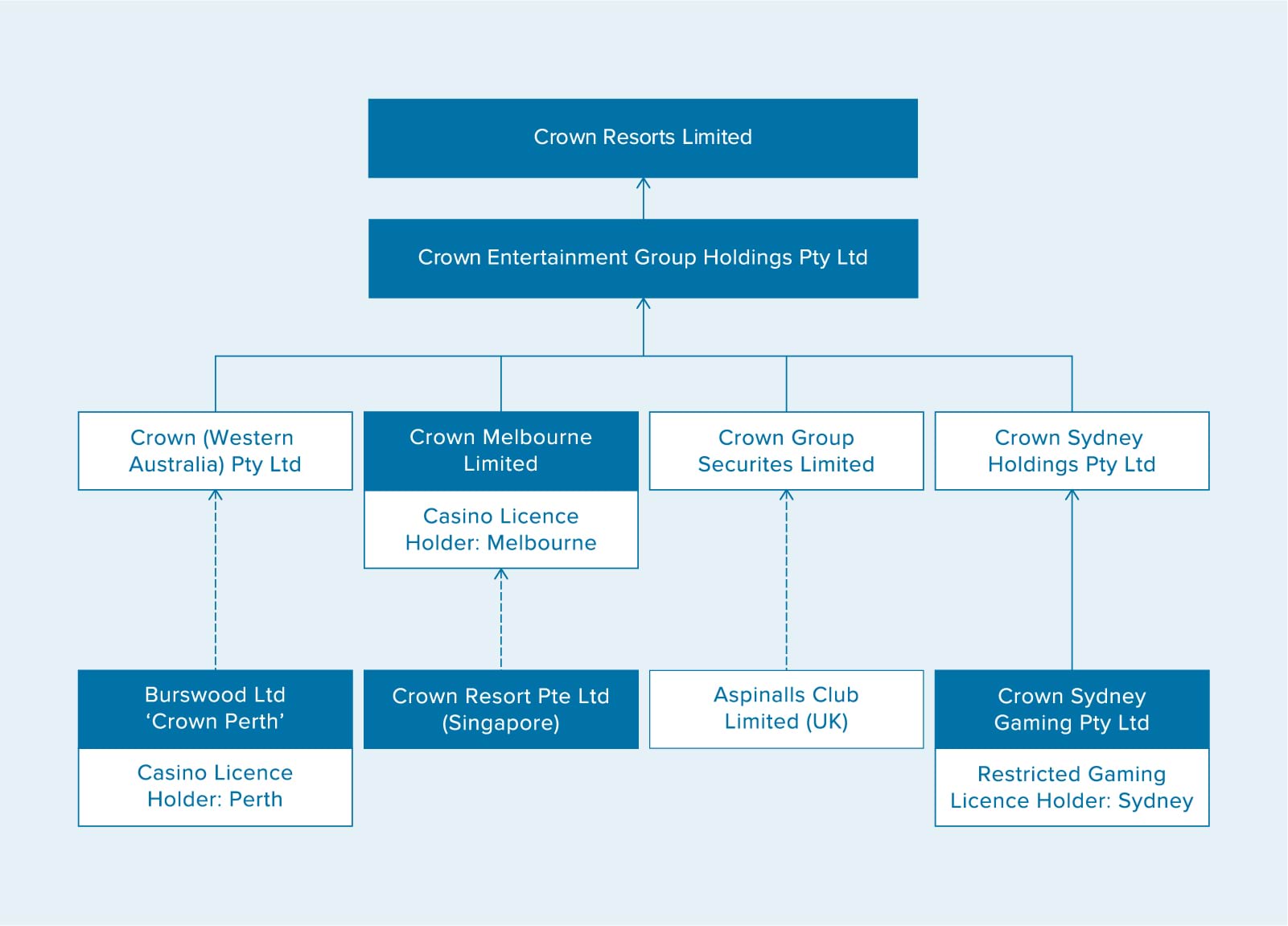

Crown group corporate history

- The corporate history of the Crown group is complex.

- This history is complicated by the names under which the corporation today known as Crown Melbourne Limited has been registered. The names include Haliboba Pty Ltd, Crown Casino Ltd and Crown Limited. Crown Melbourne’s current holding company, Crown Resorts Ltd, has also had different names, including Arterial Pty Ltd and Crown Limited.

- Today, the licence holder is registered under the name Crown Melbourne Limited, and its holding company is Crown Resorts Ltd.

- In this appendix, for the sake of simplicity, the licence holder will be referred to as Crown Melbourne and the holding company as Crown Resorts.

- Crown Melbourne was the joint venture vehicle of HCL, Federal Hotels and CUB to acquire the casino licence for the Melbourne Casino.

- The casino licence was granted on 19 November 1993.

- Crown Melbourne was listed on the ASX on 9 March 1994.1

- In June 1999, Crown Melbourne merged with PBL, a company then controlled by Mr Kerry Packer and later his son, Mr James Packer.

- The merger involved several steps. Initially, PBL acquired all the shares in Crown Melbourne. It offered ‘one PBL share for each 11 Crown [Limited] shares’.2 The Crown/PBL merger received the necessary regulatory and shareholder approvals and took effect on 30 June 1999.3

- Then, pursuant to two schemes of arrangement approved by the Supreme Court of Victoria on 21 January 2000, shareholders in HCL acquired shares in PBL at a ratio of two PBL shares for three HCL shares.4

- On the completion of the merger, Crown Melbourne:

- ceased to be a listed company

- became a wholly owned subsidiary of PBL.

- In September 2004, PBL acquired all the shares in Burswood Limited, the holding company of Burswood Nominees Pty Ltd, which held the Perth Casino licence.

- On 8 May 2007, PBL announced that it proposed to separate its gaming and media businesses into two separate listed companies, Crown Resorts and Consolidated Media Holdings.5

- The separation occurred pursuant to two schemes of arrangement, each approved by the Federal Court of Australia on 28 November 2007.6

- On the implementation of the schemes:

- Consolidated Media Holdings acquired PBL’s media assets

- Crown Resorts acquired all of PBL’s gaming businesses, including its shares in Crown Melbourne.

- On 3 December 2007, the shares in Crown Resorts were listed on the ASX.7

- On 17 October 2013, a subsidiary of Crown Resorts, Crown Sydney Gaming Pty Ltd, was incorporated to construct and operate the casino at Barangaroo in Sydney.8

- A simplified diagram of the corporate structure is set out below.

- The following were the directors of Crown Resorts who have recently resigned. Most were appointed by or connected with CPH or the Packer family:

- Ms Helen Coonan

- Mr Michael Johnston

- Mr Guy Jalland

- Mr Andrew Demetriou

- Mr Ken Barton

- Mr Harold Mitchell

- Mr John Poynton

- Mr John Horvath.9

- The current directors of Crown Resorts and those nominated, awaiting regulatory approvals, are:

- Dr Zygmunt (Ziggy) Switkowski

- Ms Antonia Korsanos

- Mr Nigel Morrison

- Ms Jane Halton.

- The following were the directors of Crown Melbourne who have recently resigned. Most were appointed by or connected with CPH or the Packer family:

- Mr Demetriou

- Mr Barton

- Mr Horvath.10

- The current directors of Crown Melbourne and those nominated, awaiting regulatory approvals, are:

- Ms Korsanos

- Mr Morrison

- Mr Bruce Carter

- Mr Stephen McCann

- Ms Halton.

Endnotes

1 Exhibit RC1610 Article: Crown at a 34pc Premium on Debut, 10 March 1994.

2 VCGA, Third Triennial Review of the Casino Operator and Licence (Report, June 2003) 32.

3 VCGA, Third Triennial Review of the Casino Operator and Licence (Report, June 2003) 32.

4 Re Hudson Conway Ltd (Nos 6484 and 6485 of 1999) (2000) 33 ACSR 657.

5 Exhibit RC1597 Article: Packer Punts on PBL Split, 9 May 2007.

6 Re Publishing & Broadcasting Ltd [2007] FCA 1610.

7 Crown Resorts, ‘Crown Announces Full Year Results’ (ASX Media Release, 20 August 2008) 2.

8 Exhibit RC0445 Bergin Report Volume 1, 1 February 2021, 101 [4].

9 Mr Horvath was an independent director.

10 Mr Horvath was an independent director.

Appendix F

Appendix F

Bergin Inquiry recommendations

It is recommended that:

- Section 4A of the Casino Control Act be amended to include an additional object of: Ensuring that all licenced casinos prevent any money laundering activities within their casino operations.

- The Independent Casino Commission (ICC) be established by separate legislation as an independent, dedicated, stand-alone, specialist casino regulator with the necessary framework to meet the extant and emerging risks for gaming and casinos.

- The ICC have the powers of a standing Royal Commission comprised of Members who are suitably qualified to meet the complexities of casino regulation in the modern environment.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to make clear that any decision about a casino licence and any disciplinary action that may be taken against a licensee is solely that of the ICC, and that any term of a regulatory agreement that has been entered into by the Government or the Authority is of no effect to the extent that it purports to fetter any power of the ICC arising under the Casino Control Act.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to ensure that the casino supervisory levy is paid to the ICC or recognised in the budget of the ICC.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to make provision for each casino operator to be required to engage an independent and appropriately qualified Compliance Auditor approved by the ICC, to report annually to the ICC on the casino operator’s compliance with its obligations under all regulatory statutes both Commonwealth and State in particular the Casino Control Act, the Casino Control Regulation and the terms of its licence.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to make provision in respect of the Compliance Auditor’s obligations in line with the following:

- If the Compliance Auditor, in the course of the performance of the Compliance Auditor’s duties, forms the belief that:

- activity within the casino operations may put the achievement of any of the objects of the Casino Control Act at risk; or

- a contravention of the Casino Control Act or the regulations or of any other Commonwealth or New South Wales Act regulating the casino operations has occurred or may occur;

the Compliance Auditor must immediately provide written notice of that belief concurrently to the casino operator and to the ICC.

- If the Compliance Auditor, in the course of the performance of the Compliance Auditor’s duties, forms the belief that:

- Consideration be given to an amendment to the Casino Control Act to include a provision similar to Singapore legislation for the concurrent reporting by the casino operator of suspicious transactions to AUSTRAC and the ICC.

- The Authority consider amendment to casino operators’ licences to impose an obligation to monitor patron accounts and perform heightened customer due diligence, the breach of which provisions will be regarded as a breach of the Licence and give rise to possible disciplinary action.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to impose on casino licensees an obligation that they require a Declaration of Source of Funds for any cash over the amount as determined by the ICC modelled on the reform introduced in British Columbia discussed in Chapter 5.1.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to prohibit casino operators in New South Wales from dealing with Junket operators.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to impose on any applicant for a casino licence an express requirement to prove that it is a suitable person by providing to the ICC ‘clear and convincing evidence’ of that suitability. This should apply to all suitability assessments under the Casino Control Act, including in the context of retaining a casino licence or in any five yearly review or for approval as a close associate.

- The definition of ‘close associate’ under the Casino Control Act be repealed and replaced to mean:

- any company within the corporate group of which the licensee or proposed licensee (Licensee) is a member;

- any person that holds an interest of 10 per cent or more in the Licensee or in any holding company of the Licensee (‘holding company’ as defined in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) so as to capture all intermediate holding companies);

- any director or officer (within the meaning of those terms as defined in the Corporations Act) of the Licensee, of any holding company, or of any person that holds an interest of 10 per cent or more in the Licensee or any holding company; and

- any individual or company certified by the Authority as being a ‘close associate’.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to include a provision that the cost of the investigation and determination of the suitability of any close associate of any applicant for a casino licence or any existing casino licensee be paid to the ICC in advance of the investigation and determination in the amount assessed by the ICC. Such amendment should include a provision for repayment of any over-estimate or payment of any shortfall against the estimate made by the ICC before the publication of the ICC’s determination.

- Item 4 of Schedule 1 of the Casino Control Act be amended to ensure that any transaction involving the sale or purchase of an interest in an existing licensee or any holding company of a licensee which results in a person holding an interest of 10 per cent or more in a licensee or holding company of the licensee is treated as a ‘major change’ event.

- The Casino Control Act be amended to provide that a person may not acquire, hold or transfer an interest of 10 per cent or more in a Licensee of a casino in New South Wales or any holding company of a Licensee without the prior approval of the ICC.

- An amendment be made to section 34 of the Casino Control Act to permit the regulator to apply to the Court for an injunction to restrain ‘any person’ in respect of a breach of the above recommended provision or to obtain appropriate orders in connection with an interest acquired, held or transferred in breach of the provision.

- The ‘gaming and liquor legislation’, as defined in section 4 of the Gaming and Liquor Administration Act 2007 (NSW) be reviewed for the purpose of considering amendments to ensure clarity and certainty in relation to the powers to be given to the new independent specialist casino regulator and consequential enactment of amendments to relevant legislation.

- In any legislative review and/or consideration of legislative powers for the ICC, it would be appropriate to consider an express provision to include ASIC as one of the relevant agencies to which the ICC may refer information. It would also be appropriate to consider the inclusion of any other relevant agency not already expressly included in the legislation.

Appendix G

Appendix G

Crown breaches

- On 10 March 2021, the Commission wrote to Crown Melbourne asking it to disclose whether, since 1 January 2010, it had engaged in conduct that would, or might, breach any provision of the:

- Casino Control Act

- Management Agreement Act

- Gambling Regulation Act

- Gambling Regulations

- AML/CTF Act

- AML/CTF Rules

- FTR Act

- Casino Agreement

- Management Agreement

- Casino Licence granted on 19 November 1993.1

- Crown Melbourne provided the information in four tranches.2 The information identified many thousands of actual or potential breaches. Most of them were not significant breaches.

- The actual or potential breaches can be divided into four broad categories:

- RSG

- conduct of gaming

- AML and CTF

- minor regulatory and other miscellaneous breaches.

- They are summarised in the following tables.

Responsible service of gambling

- This table sets out actual or potential breaches of the Gambling Regulation Act, Casino Control Act or Crown Melbourne’s Gambling Code.

Conduct of gaming

- This table sets out the actual or potential breaches of an ICS, the Casino Control Act, Management Agreement Act, Gambling Regulation Act or the Gambling Regulations.

AML/CTF

- This table sets out the actual or potential breaches of the AML/CTF Act, AML/CTF Rules, FTR Act, Casino Control Act or the Management Agreement Act.

Minor regulatory and miscellaneous breaches

- This table sets out actual or potential breaches of the Gambling Regulation Act, Gambling Regulations, Casino Control Act or the Management Agreement Act. It also includes actual or potential breaches of Crown Melbourne’s ICSs, Standard Operating Procedures, Casino Licence and the Casino Agreement.

Endnotes

1 Exhibit RC0148 Letter from Solicitors Assisting to the Directors, Crown Melbourne, 10 March 2021.

2 Exhibit RC0149 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 24 March 2021; Exhibit RC0149 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 24 March 2021, Annexure a; Exhibit RC0149 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 24 March 2021, Annexure b; Exhibit RC0244 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 21 April 2021; Exhibit RC0244 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 21 April 2021, Annexure a; Exhibit RC0244 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 21 April 2021, Annexure b; Exhibit RC0244 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 21 April 2021, Annexure c; Exhibit RC1562 Email from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 19 May 2021; Exhibit RC1562 Email from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 19 May 2021, Annexure a; Exhibit RC1563 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 18 June 2021; Exhibit RC1564 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 23 June 2021.

3 Exhibit RC0244 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 21 April 2021, 2.

Appendix H

Appendix H

Suitability and public interest

Previous legal advice or consideration of the term ‘suitability’

- When the regulator conducted its First triennial review of the Casino Operator and Licence in 1997 (First Review), it sought advice from Ms Susan Crennan, QC (as her Honour then was) on the proper construction of terms used in section 9 of the Casino Control Act. As these terms and their definitions have not been amended since, the advice may be considered relevant.

- Ms Crennan, QC provided the following advice:

[Suitable person]

There are no mandatory considerations set out in section 25 but a ‘suitable person to be concerned in or associated with the management and operation of a casino’ (s. 9) and ‘a suitable person to continue to hold the casino licence’ (s. 25) must give rise to very similar if not identical considerations.

Suitability

… ‘ Suitable person to continue to hold the casino licence’ in section 25, in my opinion, should similarly be construed to mean a person who is both ‘fit and proper’ and ‘operationally capable’ …

Accordingly any matter relevant to a person being:

- fit and proper; and

- operationally capable;

may be taken into account in determining whether a person is a ‘suitable person to continue to hold the casino licence’ under the provisions of section 25. … There is no other test as such, as to whether persons meet the standards however guidance from the cases would suggest that on a proper analysis the basic test is whether the [regulator] achieves the requisite satisfaction that there is nothing which reflects adversely on the operator’s fitness to operate a casino (citations omitted).

…

Good repute

Advice has already been provided by me on 26 May 1993 as to construction to be given to ‘good repute’ in section 9(2) of the [Casino Control] Act. On that occasion I opined that ‘good repute’ in section 9(2) should be construed widely, not narrowly, and would include ‘reputation in fact and reputation in merit’ the distinction between those being further explained in that advice.

…

Character

The word has as one of it[s] ordinary meanings ‘the mental or moral constitution of a person’ (Oxford English Dictionary [citation omitted]). To say a person has ‘character’ or ‘good character’ implies ‘good repute’ so there is some degree of overlap. Equally ‘bad character’ can imply ‘bad repute’.

Honesty

Because ‘honest’ and ‘dishonest’ are descriptions of conduct frequently used in the law and in the case of ‘dishonest’ particularly in the criminal law, ‘honesty’ is a word possibly narrower and clearer that the words ‘character’ and ‘integrity’. ‘Honesty’, in the prevailing modern sense of the word, means ‘uprightness of disposition and conduct; integrity; truthfulness; straightforwardness; the quality opposed to lying, cheating or stealing’ (Oxford English Dictionary [citation omitted]).

…

Integrity

Integrity means ‘freedom from moral corruption’. It is a synonym for honesty. It carries with it the connotation of truthfulness and fair dealing (Oxford English Dictionary [citation omitted]).

…

[Reputation]

Innuendo and rumour are matters which go to ‘reputation in fact’ as described in my earlier advice. To ensure that real (or actual) issues are not clouded by innuendo and rumour it is appropriate to investigate innuendo and rumour to see whether such have a basis in fact. In the absence of a proper factual basis, innuendo and rumour cannot in fairness be given any significant weight at all.1

Mr David Habersberger, QC (as his Honour then was) separately advised the regulator on the extent of the investigation required by section 25 of the Casino Control Act. With respect to the suitability review, he advised:

It is clear that the first limb of s. 25(1) requires an investigation of the suitability of the casino operator, which includes its associates. This is a similar test to that laid down in s. 9(1) of the [Casino Control] Act, as amplified by the particular matters listed in s. 9(2), and would have been applied by the [regulator] before it granted Crown Casino Ltd (‘Crown’) its casino licence in November 1993. The first limb of [s. 25(1)] is also virtually the same test as that specified in s. 20(1)(d) as a ground for disciplinary action. In essence, one could say that s. 25(1)(a) is a further attempt at ‘ensuring that the management … of casinos remains free from criminal influence or exploitation’ (see 1(a) of the [Casino Control] Act).

Therefore, in my opinion, the [regulator] need to go no further than s. 9(2)(a) to (g) for guidance as to what matters it would have to consider in forming the opinion required under s. 25(1)(a)—whether the casino operator and its associates were still persons of good repute, having regard to character, honesty and integrity, whether they were still persons of sound and stable financial background, whether the casino operator still had a satisfactory ownership, trust or corporate structure, whether it still had adequate financial resources and sufficiently experienced staff, whether its business ability was such that it was maintaining a successful casino, whether there were any business associations with any persons or bodies who were not of good repute or who had undesirable or unsatisfactory financial resources and whether all relevant officers were still suitable persons to act in their particular capacities.2

- In the Fifth Review of the Casino Operator and Licence, the VCGLR referred to advice that had been previously received as to the meaning of ‘suitable person’, which stated:

The expression ‘suitable person’ is not defined in the Casino Control Act. The VCGLR and its predecessors have obtained advice from Senior Counsel that, in light of the objectives of the Casino Control Act, the task of determining suitability for a section 25 casino review is akin to determining suitability for approval of an application for a casino licence.3

- The Bergin Report also considered the term ‘suitability’, noting:

Previous reports to the [ILGA] have explored the expression ‘good repute having regard to character, honesty and integrity’. Comparisons have been made with tests of fitness and propriety to hold certain licences, and requirements to be of ‘good fame and character’.

Reference has also been made to judicial observations in relation to the concepts of ‘character’ as it ‘provides an indication of likely future conduct’ and of ‘reputation’ as it ‘provides an indication of public perception as to the likely future conduct’ of a person. It has also been observed that findings as to character and reputation ‘may be sufficient’ to ground a conclusion that a person is not ‘fit and proper to undertake activities’. The analysis of the concept of character can become somewhat circular with reference to a person’s ‘nature and good character’. However, it is clear that a person of good character would possess ‘high standards of conduct’ and act in accordance with those standards under pressure.

Some observations by Regulators in other jurisdictions when considering a casino operator’s ‘integrity, honesty, good character and reputation’ are of assistance.

In 1981 the New Jersey Casino Control Commission made the following observation in relation to the assessment of ‘character’ in the context of individuals:

We find this a most difficult task for several reasons. First, ‘character’ is an elusive concept which defies precise definition. Next, we can know the character of another only indirectly, but most clearly through his words and deeds. Finally, the character of a person is neither uniform nor immutable.

Nevertheless, we conceive character to be the sum total of an individual’s attributes, the thread of intention, good or bad, that weaves its way through the experience of a lifetime.

In 2018 the Massachusetts Gaming Commission observed that when assessing the suitability of a corporate casino operator, it must be remembered that ‘the corporate entity itself is made up of individuals and has no independent character or morality standing alone’. The Commission referred to the remarks in Merrimack College v KPMG LLP … that:

Where the plaintiff is an organization that can only act through its employees, its moral responsibility is measured by the conduct of those who lead the organisation. Thus, where the plaintiff is a corporation … we look to the conduct of senior management—that is, the officers primarily responsible for managing the corporation, the directors, and the controlling shareholders, if any.

It is accepted that a company’s suitability may ebb and flow with changes to the composition of the company’s Board and Management, and others who influence its affairs, over time. If a company’s character and integrity has been compromised by the actions of its existing controllers, then it may be possible for a company to ‘remove a stain from the corporate image by removing the persons responsible for the misdeeds.’ However, this would only be possible if the company could ‘isolate the wrong done and the wrongdoers from the remaining corporate personnel’. It would be necessary to ensure that ‘the corporation has purged itself of the offending individuals and they are no longer in a position to dominate, manage or meaningfully influence the business operations of the corporation.’

A person is of ‘good repute’ if they have a reputation or are known to be a good person. A person may have flaws and may make mistakes but still have a reputation or be known as a good person. They may be of ‘good repute’ because they are honest; because they have integrity; and because their character is not adversely affected by the particular mistakes they have made.

In the context of this Inquiry good repute or reputation is to be judged by reference to matters including character, honesty and integrity. Although there was some debate about whether the assessment of good repute includes consideration of matters other than character, honesty and integrity, it is necessary in assessing character to take an ‘holistic view’ of both the Licensee and Crown including the assessment of the integrity of corporate governance and risk management structures and the adherence to adopted policies and procedures.4

Public interest

- In conducting its First Review, the VCGA also sought advice from Mr Habersberger, QC on the extent of the investigation required by section 25 of the Casino Control Act. Mr Habersberger, QC advised:

Understanding what is required by the second limb of s.25(1) is rather more difficult [than understanding the first limb of s.25(1)]. A number of points can be made concerning its construction. First, the phrases ‘public interest’ or ‘interest of the public’ are defined for the purposes of the [Casino Control] Act in s.3(1) thereof as meaning:

[the] public interest or interest of the public having regard to the creation and maintenance of public confidence and trust in the credibility, integrity and stability of casino operations.

In my opinion, this definition of the phrase ‘public interest’ is quite restricted compared to what it might have been thought to encompass without the enforced statutory guidance. It is limited to certain aspects of ‘casino operations’ rather than a broader approach to the question of the ‘public interest’.

Secondly, there can be no doubt that the subject matter of s.25(1)(b), whatever that may be, is not the same as that in s.25(1)(a) of the [Casino Control] Act.

Thirdly, the distinction between casino operator and casino operations is to be found in the [Casino Control] Act itself. Part 3 of the [Casino Control] Act is concerned with the ‘Supervision and Control of Casino Operators’, whereas Part 5 deals with ‘Casino Operations’.

Next, the question for the [regulator] under the second limb of s.25(1) is whether ‘the casino licence’ should continue in force, that is the licence of a particular casino operator, in this case, Crown. It is not a direction to the [regulator] to embark on the task of deciding whether or not there should be any, or any particular number of, casinos in Victoria. Moreover, the question is whether the licence ‘should continue in force’, that is, whether or not there should be a licence.5

- Ms Crennan, QC also commented on the public interest requirement in section 25(1) of the Casino Control Act in her advice to the VCGA in the First Review. She advised:

Community standards whether consensual or legal are relevant as guidelines or specific standards of good repute, character, honesty or integrity. It is Australian standards i.e. [those] recognised by the Australian community which are relevant. ‘Public interest’ which is relevant to section 25(2) is defined in section 3 and includes as a legitimate object of public interest ‘public confidence and trust in the credibility, integrity and stability of casino operations’ must refer to the confidence of the public in Victoria. Arguably the standards imposed under the Victorian and New South Wales legislation may be higher in some respects than standards imposed under other Australian legislation bearing in mind the derivation from the New Jersey model of legislation. See for example Darling Casino v. New South Wales Casino Control Authority and Ors., an unreported decision of the High Court dated 4 April 1997 at pp.26–32. Be that as it may and I have not made any detailed comparisons for the purposes of this advice, it seems to me the public confidence referred to in section 3 must be a reference to local confidence which in turn will be grounded in local community standards. Standards may well be different in different countries and cultures but I do not deal with that further having regard to what I have said about the relevant community standards.6

- In the Fifth Review, the VCGLR noted that senior counsel’s advice on the definition of the phrase ‘public interest’ is:

… quite restricted compared to what it might have been thought to encompass without the enforced statutory guidance. It is limited to certain aspects of ‘casino operations’ rather than a broader approach to the question of the ‘public interest’.7

Endnotes

1 VCGA, Second Triennial Review of the Casino Operator and Licence (Report, June 2000) 49–53.

2 VCGA, Second Triennial Review of the Casino Operator and Licence (Report, June 2000) 54–5.

3 Exhibit RC0013 VCGLR Fifth Review of the Casino Operator and Licence, June 2013, 43.

4 Exhibit RC0970 Bergin Report Volume 2, 1 February 2021, 337–8 [11]–[18] (citations omitted).

5 VCGA, First Triennial Review of the Casino Operator and Licence (Report, June 1997) 5.

6 VCGA, Second Triennial Review of the Casino Operator and Licence (Report, June 2000) 52–3.

7 Exhibit RC0013 VCGLR Fifth Review of the Casino Operator and Licence, June 2013, 141.

Appendix I

Appendix I

Special Manager requirements

General

- The Special Manager must consider:

- whether there is any evidence of maladministration

- whether there is any evidence of illegal or improper conduct

- whether Crown Melbourne has engaged in conduct that may give rise to a material contravention of any law

- the conduct of the casino operations generally since the conclusion of the Commission.

- The Special Manager’s report must:

- contain details of each direction given by the Special Manager

- state whether the direction was complied with

- state whether Crown Melbourne’s directors and executives cooperated with the Special Manager in the performance of its functions.

Risk management

- The Special Manager is to evaluate whether:

- Crown Melbourne has conducted a suitable ‘root cause’ analysis into the failures outlined in the Report and in the Report of this Commission

- Crown Melbourne has implemented, completely and effectively, the recommendations made by Mr Peter Deans in his Expert Report on the Risk Management Frameworks and Systems of Crown Resorts Limited1

- an external review has been undertaken of the robustness and effectiveness of Crown Melbourne’s risk management framework, systems and processes, and their appropriateness to Crown Melbourne as a casino operator, and whether any recommendations made as a result of that review have been implemented completely and effectively.

Culture

- The Special Manager is to determine whether Deloitte has completed Phase 4 of its Project Darwin and is to evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of Crown’s cultural reform program.

Anti-money laundering/counter-terrorism financing

External report recommendations

- The Special Manager is to evaluate whether there has been effective implementation of the recommendations set out in the following reports:

- Promontory Phase 1 Report dated 24 May 2021 and titled ‘Phase 1: AML Vulnerability Assessment’.2 The recommendations are set out in section 4.

- Promontory Phase 2 Draft Report dated 20 June 2021 and titled ‘Strategic Capability Assessment’.3 This report sets out a forward-looking strategic assessment and articulation of a ‘target state model’ for Crown Resorts to achieve in order to manage financial crime risk.

The Special Manager is to assess whether Crown’s financial crime workforce numbers, structures, roles and functions correspond with the ‘target state’ articulated in this report.

- Deloitte Phase 1 Report dated 26 March 2021 and titled ‘Assessment of Patron Account Controls’.4 The recommendations are summarised in a report dated 13 April 2021 titled ‘Phase 1: Assessment of Patron Account Controls—Assessment of Crown’s Response’.5

- Deloitte Phase 2 Report concerning a Forensic Review of Crown’s Patron Accounts. The details of the Phase 2 Forensic Review are set out in Deloitte’s engagement letter dated 22 February 2021.6

- Deloitte Phase 3 Report concerning a Further Controls Assessment. The details of the Further Controls Assessment are set out in Deloitte’s engagement letter dated 22 February 2021.7

- Deloitte Report on Hotel Card Transactions Review. The details of the Hotel Card Transaction Review are set out in a document dated 8 July 2021 and titled ‘Forensic Review: Updated Timings for Phase 2 and 3 of Forensic Review (including HCT matter)’.8

- Initialism Transaction Monitoring Review dated June 2021.9 The recommendations are on pages 6, 14, 28–9, 37–8 and 44.

McGrathNicol report

- McGrathNicol’s Forensic Review dated July 2021 identified preliminary indications of ‘structuring’ and ‘parking’ (being money laundering techniques) on Crown Melbourne’s DAB accounts.10

- McGrathNicol recommended further investigation of those transactions and the suspected structuring and parking.

- The Special Manager is to determine whether the further investigation has occurred and, if so, whether any changes to Crown’s AML/CTF Program are necessary and have been implemented.

Crown’s Financial Crime and Compliance Change Program

- Crown’s Financial Crime and Compliance Change Program (FCCCP) is set out in a document prepared by Mr Steven Blackburn, Crown’s Group Chief Compliance and Financial Crime Officer, dated 24 May 2021.11 The FCCCP focuses on 10 key areas for uplifting Crown’s financial crime and compliance performance; namely people, risk appetite, frameworks, risk assessments, reporting and oversight, assurance, training, roles and responsibilities, customers and controls, and data and systems.

- The Special Manager is to evaluate whether all the recommended reforms set out in the FCCCP (and any additions to that program) have been effectively implemented.

Other external expert work

- The Special Manager is to evaluate whether there has been effective implementation of any recommendation, whether or not set out in a report, in respect of the following work:

- PwC Australia’s work for Crown concerning an uplift in Crown’s SMR reporting, TTR reporting and/or IFTI reporting;

- Allens Linklaters’ work for Crown concerning an uplift in Crown’s SMR reporting, TTR reporting and/or IFTI reporting; and

- an enterprise-wide risk assessment.

Resourcing

- The Special Manager is to assess the adequacy of Crown Melbourne’s financial crime budget.

- The Special Manager is to assess the adequacy of the staff numbers in the financial crime group.

AML/CTF Program

- The Special Manager is to evaluate whether the Crown Melbourne board is providing effective and meaningful oversight of its AML/CTF Program.

- The Special Manager is to assess whether Crown Melbourne is complying with its AML/CTF Program.

- The Special Manager is to review any internal or external audits conducted on any part of Crown Melbourne’s AML/CTF Program and evaluate whether any non-compliance identified has been remedied.

Responsible service of gambling

- The Special Manager is to assess Crown Melbourne’s responsible service of gambling program. This assessment should include examining:

- the effectiveness of Crown Melbourne’s staff training in the responsible service of gambling;

- the adequacy of the responsible service of gambling staff numbers;

- the adequacy of funding of Crown Melbourne’s responsible service of gambling program;

- the effectiveness of the services provided by the responsible service of gambling staff;

- the effectiveness of Crown Melbourne’s Self-Exclusion Program and related programs (for example Time Out);

- the effectiveness of the responsible service of gambling ‘enhancements’ approved in May 2021;12 and

- whether Crown Melbourne complies with its Gambling Code and Play Periods Policy.

Compliance with statutory and contractual obligations

- The Special Manager is to review whether Crown Melbourne complies with its obligations under the Casino Control Act, the Gambling Regulation Act, the Casino Agreement and the Management Agreement.

Definitions

- The following definitions apply to the terms in this document:

- AML/CTF means Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing.

- Casino Agreement means the agreement between the regulator (then known as the Victorian Casino Control Authority) and Crown Melbourne (then known as Crown Casino) on 21 September 1993 as amended from time to time.

- Crown Melbourne means Crown Melbourne Limited.

- DAB means deposit account balance.

- IFTI means international funds transfer instruction.

- Management Agreement means the agreement between the State and Crown Melbourne (then known as Crown Casino) on 20 April 1993 as amended from time to time.

- SMR means suspicious matter report.

- TTR means transaction threshold report.

Whenever the Special Manager is required to report on the implementation of recommendations or reforms, the Special Manager should also report on the implementation of any variation to those recommendations or reforms.

Endnotes

1 Exhibit RC0971 Peter Deans Expert Report on the Risk Management Frameworks and Systems of Crown Resorts Limited, 29 June 2021.

2 Exhibit RC0100 Promontory Phase 1: AML Vulnerability Assessment, 24 May 2021.

3 Exhibit RC0397 Promontory Phase 2: Strategic Capability Assessment Report, 20 June 2021.

4 Exhibit RC0084 Statement of Lisa Dobbin, 16 April 2021, Annexure e.

5 Exhibit RC0084 Statement of Lisa Dobbin, 16 April 2021, Annexure f.

6 Exhibit RC0084 Statement of Lisa Dobbin, 16 April 2021, Annexure a; see in particular Appendix 1. The terms of the engagement were varied by letter dated 19 March 2021: Exhibit RC0084 Statement of Lisa Dobbin, 16 April 2021, Annexure b. See also the detail in Exhibit RC0476 Deloitte Crown Resorts Updated Timing for Phase 2 and 3 of Forensic Review, 30 June 2021.

7 Exhibit RC0084 Statement of Lisa Dobbin, 16 April 2021, Annexure a; see in particular Appendix 1. The terms of the engagement were varied by letter dated 19 March 2021: Exhibit RC0084 Statement of Lisa Dobbin, 16 April 2021, Annexure b.

8 See Exhibit RC0476 Deloitte Crown Resorts Updated Timing for Phase 2 and 3 of Forensic Review, 30 June 2021 for details on the scope of this work and report.

9 Exhibit RC1351 Initialism Transaction Monitoring Review Crown Resorts, June 2021.

10 Exhibit RC1460 McGrathNichol Forensic Review AML/CTF Report, 19 July 2021.

11 Exhibit RC0311 Further Supplementary Statement of Steven Blackburn, 7 June 2021, Annexure a.

12 Exhibit RC0696 Minutes of Crown Resorts board meeting, 24 May 2021; Exhibit RC0122 Letter from Allens Linklaters to Solicitors Assisting, 26 May 2021.

Appendix J

Appendix J

Best practice in gambling regulation: international comparison

Introduction

- This appendix will review the regulation of casinos in a number of jurisdictions. Particular attention will be given to the different approaches taken to:

- the type and role of the regulator

- the enforcement powers conferred on the regulator

- AML

- junkets

- assessing the suitability of the casino operator.

Type and role of regulator

- Governments regulate casino gaming through statutory authorities that have powers to enforce gaming legislation and oversee the operations of the casino.

- There are three categories of statutory authorities:

- a standalone authority

- a general gaming authority

- a mixed licensing authority.

- New Jersey and Singapore have standalone casino regulators: the New Jersey Casino Control Commission (NJCCC) and the Singaporean CRA. These bodies oversee aggressive regulatory regimes.1

- The NJCCC has broad-ranging powers. It can hear and determine applications for a casino licence, make regulations with which a casino operator must comply and work with the Division of Gaming Enforcement (Division).2 The Division is best described as the investigatory and disciplinary arm of the casino regulatory system in New Jersey.3 It is responsible for enforcing the Casino Control Act 2021 (New Jersey) and the regulations made under it.4 The Division also conducts continuing reviews of casino operations through on-site observation and other reviews.5

- The rationale for New Jersey’s standalone regulator and its strict regulatory approach can be traced back to the legalisation of casinos in that state in the 1970s. In 1974, New Jersey voters rejected a ballot initiative to legalise casino gambling statewide. In 1976, voters approved a more restrictive referendum to legalise casino gaming in Atlantic City. The objective was to revitalise Atlantic City and provide economic support for older people and people with disability through taxation.6

- New Jersey policymakers were keen to restrict the influence of gaming and ensure tight regulations around the operation of casinos.7 This approach was described by Professor Anthony Cabot in evidence given at the Bergin Inquiry. He said:

New Jersey—I think there was a bit of hostility towards the gaming industry at the state level when it first started and they took a position that they were going to be the most rigid regulatory agency in the world at the time. And so they came out and started regulating the industry in a fairly draconian fashion where they tried to regulate virtually everything down to, you know, the colour of the carpet.8

- In contrast, Nevada’s approach to casino regulation has been described as ‘hands off’.9 Nonetheless its focus, the suitability of the operator, has been credited as successfully eliminating the influence of organised crime.10

- Nevada has two separate regulatory agencies: the Nevada Gaming Control Board and the Nevada Gaming Commission. The Nevada Gaming Control Board is a full-time regulatory agency that oversees the gaming industry in the state.11 It has several divisions, including an investigations unit that conducts investigations related to casino licence applications and assesses suitability.12 The Nevada Gaming Commission is a part-time body that hears appeals from decisions of the Nevada Gaming Control Board and has original jurisdiction in some licensing matters.13

- Most other jurisdictions have a single gaming regulator with responsibility for regulating casinos, electronic and sports gaming, and lotteries. For example, in New Zealand the Gambling Commission oversees larger-scale lotteries, gaming machines and casinos.14 It determines casino licence applications as well as appeals relating to licences to operate gaming machine venues and gaming activities such as larger-scale lotteries and raffles.15 Single gaming regulators also exist in Massachusetts (the Massachusetts Gaming Commission (MGC)) and the United Kingdom (Gambling Commission).

- Alberta has a single mixed licensing regulator, the Alberta Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Commission (AGLC). The AGLC administers the Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act 2000 (Alberta), including the licensing of the sale and distribution of liquor and cannabis.16

Enforcement powers

- All regulators have investigative and disciplinary powers that are necessary to enforce the local gaming statutes and regulations. The powers vary in scope.

- Several regulators have the power to enter a casino to observe whether the operator is conducting its operations in accordance with the regulations. In Alberta, a licensed inspector from the AGLC may enter any gaming premises to ensure compliance with the Alberta Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act.17 The inspector is not required to give notice of an inspection. The only limitations are that the inspection must occur at a ‘reasonable time’, and the inspector must carry the required identification and present it on request to the owner or occupant of the premises being inspected.18

- As an adjunct to an entry power, some regulators have powers to inspect and impound the books and records of a casino as well as gaming equipment. In New Jersey, the Division can, with the approval of the Division’s director:

- inspect, examine and impound any gaming devices and equipment

- inspect, examine and audit any books, records and documents relating to a casino operator’s operations

- seize, impound or take physical control of any book, record, ledger, game, device, cash box and its contents, counting room or its equipment, or casino operations.19

- Some jurisdictions permit the regulator to demand the production of documents or the provision of information. For example, in New Zealand, under the Gambling Act 2003 (NZ), an inspector from the Gambling Commission may serve a notice on any person requiring them to provide or produce to the inspector any information, class of information or documents requested.20

- Other jurisdictions impose an obligation on the casino operator to cooperate with or be candid in their dealings with the regulator. For example, the New Jersey Casino Control Act requires ‘each licensee or registrant, or applicant for a [licence] or registration … [to] cooperate with the division in the performance of its duties’.21 The Massachusetts General Laws 2020 (Massachusetts) criminalise both a lack of cooperation with, and making false statements to, the MGC. The penalty is a maximum of five years’ imprisonment or a fine of USD25,000.

- Cooperation and candour with the regulator are sometimes imposed through disciplinary powers. In Singapore, the CRA can take disciplinary action (which includes cancelling or suspending a licence) where the casino operator has failed to provide information that the Casino Control Act 2006 (Singapore) requires, or where the casino operator has knowingly or recklessly provided false or misleading information.22 Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the Gambling Act 2005 (UK) authorises the Gambling Commission to revoke or suspend an operating licence, if the Commission believes that the operator has failed to cooperate with a statutory review process.23

- Many jurisdictions in the United States of America classify their gaming or casino regulators as law enforcement agencies, and give them corresponding powers.

- In Massachusetts, the MGC has an Investigations and Enforcement Bureau. Its function is to maintain the integrity of the Massachusetts gaming industry.24 The Massachusetts General Laws provide that members of the gaming enforcement unit of the State Police are to be assigned to the Bureau to investigate gaming violations by a licensee or any activity at a gaming establishment.25 In order to formalise and strengthen the partnership contemplated in the Massachusetts General Laws, the MGC and the State Police have entered into a memorandum of understanding.26 This memorandum deals with various matters such as the manner in which State Police are deployed to work with the Bureau,27 and the obligation of the MGC to pay the salaries of State Police personnel who are deployed to the Bureau in certain circumstances.28

- The Massachusetts General Laws also enable the MGC to have a permanent presence at casinos in order to exercise ‘its oversight responsibilities with respect to gaming’.29

- In New Jersey, there is significant cooperation between the Division and the Casino Gaming Bureau of the New Jersey State Police.30 The Casino Investigations Unit, a division of the Casino Gaming Bureau, has authority to prosecute offences under the New Jersey Casino Control Act and has a permanent presence at all 12 casinos in Atlantic City.31

- Regulators may rely on notification provisions to assist in enforcement. In Alberta, the Casino Terms and Conditions and Operating Guidelines (Handbook) set out the conditions of a casino licence. One condition is that the casino operator must notify the AGLC immediately if any of its officers, shareholders, directors, owners or employees are charged with or convicted of an offence under certain nominated statutes, including the Criminal Code 1985 (Canada) and the Alberta Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act.32

AML

- There are two principal approaches to managing the risks of money laundering through casinos. One method is by enacting separate legislation that imposes reporting obligations on casinos.

- In the United States of America, Title 31 of the Code of Federal Regulations 2021 (USA) requires casinos to:

- develop and implement an AML program reasonably designed to assure and monitor compliance with the requirements set out in the relevant Federal laws

- comply with specific record-keeping requirements with respect to each deposit of funds, account opened or line of credit extended

- comply with the special information-sharing procedures to deter money laundering and terrorist activity

- report any suspicious transactions relevant to possible violations of law or regulation to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.33

- The other approach, which is adopted in Alberta and the United Kingdom, is to require casinos to take certain AML action as a condition of the casino licence. In Alberta, the AGLC is a reporting entity under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act 2000 (Canada).34 In order for casinos to fulfil their obligations, the Handbook sets out requirements that each casino must meet in order to combat money laundering. These include:

- a requirement that all registered gaming workers complete an AML training course

- an obligation to identify patrons for certain cash transactions

- the appointment of AML administrators responsible for entering information into the AGLC AML database

- the development and maintenance of internal facility policy and procedures relating to AML, where the AGLC’s prior approval must be obtained for certain programs and procedures

- a prohibition on conducting denomination exchanges in excess of CAD1,000 per patron on the same gaming day

- tracking transactions that exceed CAD3,000.35

Junkets

- There are two approaches to regulating junkets:

- a regulator-centric approach

- a casino-based approach.

- A regulator-centric approach places the responsibility for regulating junkets with the regulator. Here, the regulator determines whether a junket can operate by assessing the suitability of the junket operator. Singapore and New Jersey have adopted this approach.36

- The New Jersey approach is less aggressive. The NJCCC licenses junkets as an ‘ancillary casino service industry enterprise’ and the junket operator is required to establish its good character, honesty and integrity.37 The junket operator must also provide any financial information requested.38 The NJCCC ensures that the casino operator properly supervises the junket operator by holding the casino operator responsible for any breaches of the Casino Control Act the junket operator or representative commits.39

- In Singapore, the Casino Control Act strictly regulates the licensing of junket operators, which are referred to as IMAs.40 The strict approach reflects the Singaporean government’s concern about criminal influences on junkets and the opportunity to launder money through junket operations. On the introduction of the Casino Control Bill 2006 (Singapore), the Deputy Prime Minister said:

Because of the large sums of money transacted between the junket promoters, their clients and the casinos, it is important that junket promoters are well-regulated to ensure that the junkets do not provide a cover for crime syndicates to engage in criminal activities, such as money laundering. For this reason, clause 110 of the Bill shall require junket operators to be licensed before they can work with our casinos.41

- The CRA must determine the suitability of an IMA.42 In its assessment, the CRA takes into account whether the applicant is of good character, is financially sound and stable, has a satisfactory ownership structure, has business associations with persons not of good repute or has a record of non-compliance with legal or regulatory requirements.43 The regulations require an IMA to keep extensive records of all players’ names and identity information and to provide this information to the CRA on request.44 The regime also requires the casino to certify that entering into an agreement with an IMA will not undermine the credibility, integrity and stability of casino operations.45

- The casino-based approach is applied in some jurisdictions, including Nevada. Junket operators, known as ‘independent agents’, must register with the Nevada Gaming Control Board.46 No probity assessment is required and a casino is not required to apply internal controls in engaging with the independent agent.47

- Nevada’s approach may be explained by the unique nature of independent agents:

- In relation to the internal control procedures at casinos, the contractual relationship is between the player and the casino.

- Independent agents cannot extend credit to junket players.

- Independent agents cannot take a share or commission of junket players’ actual winnings and are paid based on a theoretical earning potential.48

Suitability

- All casino regulators assess the suitability of an applicant to operate a casino, along with the suitability of the applicant’s associates. Public faith and confidence in casinos will only exist if those who are licensed to operate them, as well as their associates, are of good moral character.49

- The requirement that a casino operator be a suitable person can be traced back to the decision of the Nevada Gaming Commission to adopt a suitability requirement in response to the rising influence of organised crime in the state.50 The requirement was introduced in 1975 to ensure that a person could not operate a casino unless they:

- are of good character and reputation

- have adequate business competence and experience.51

- Most jurisdictions have suitability requirements that address three characteristics:

- character and integrity

- financial ability

- management ability.

- The character and integrity requirement takes a number of forms, but generally demands that an applicant (or an associate) be of good character. This is often regarded as someone who acts honestly and with integrity. Some jurisdictions, such as Alberta and Nevada, require the assessment to take into account previous criminal activity.52

- The financial ability assessment examines the operator’s soundness and the stability of its financial position. If a casino does not have sufficient financial support, it may turn to organised crime to help it operate.53

- The rationale for the management ability requirement is the same as for financial stability. A casino operator and its associates should be capable of managing and operating a casino to avoid nefarious organisations infiltrating it due to financial or managerial incompetence.

- The standard of proof required to meet the suitability requirement differs between jurisdictions. In Massachusetts, an applicant has the burden of proving suitability by clear and convincing evidence.54

Corporate structure

- While suitability is a key requirement in granting a licence, some jurisdictions either require the applicant to have a specific corporate structure or impose limits on the ownership structure.

- In Alberta, the Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Regulation 1996 (Alberta) provides that only a charitable or religious organisation can apply for certain gaming licences, and then only if the proceeds from gaming will be used for an approved charitable or religious purpose.55 This reflects the history of gambling in Canada, where churches and other community organisations raised funds through raffles or lotteries.56

- In Singapore, the Casino Control Act places various restrictions on share ownership. For example, it prevents substantial changes in shareholding within the first 10 years from the date on which a second site for a casino is designated under the Act.57 Thus, the principal shareholder in a casino operator cannot, without approval of the CRA, reduce its shareholding to below 20 per cent of the issued capital during that period.58 In addition, a person cannot, on or after the date a casino licence commences, acquire or enter into an arrangement to control more than 5 per cent of the issued shares in the casino operator without the Minister for Home Affairs’ approval.59 Additional approvals are required if a person seeks to control between 12 per cent and 20 per cent, or 20 per cent or more, of the issued shares.60

- The reason for these restrictions was explained by the then Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore upon the introduction of the Singapore Casino Control Bill. He said that these restrictions were required so that the regulator and the Minister would be aware of significant shareholdings and could ensure that criminals could not infiltrate the operation of a casino by controlling an interest in a casino operator.61

Associates and key personnel

- Most jurisdictions assess the suitability of those who are associated with a casino operator. This sometimes includes certain employees.

- An associate is usually defined as a person who is able to influence or control the casino operator. For example, the Gaming Control Act 2021 (Nevada) describes an affiliate as someone who is ‘directly or indirectly through one or more intermediaries, controls, is controlled by or is under common control with, [the licensee]’.62

- Under the New Zealand Gambling Act, a person is deemed to have ‘significant influence in a casino’ in circumstances that include if they:

- are a director of the company that holds the casino licence; or

- own shares (with certain voting rights), directly or indirectly, in the licence holder.63

- Another way in which the suitability criterion is applied to those associated with a casino operator is by reference to the position they hold. In Alberta, the Handbook describes the ‘key employees’ who are subject to the suitability requirement.64 They include senior management (such as the CEO or CFO), security management personnel and any person holding a position specified by the AGLC.65

- The United Kingdom has a more generalist approach. In its Licensing and Policy Statement, the Gambling Commission simply notes that it will, through the process of determining licence applications, assess the suitability of those persons ‘considered relevant to the application’.66 That will include persons exercising a function in connection with, or having an interest in, the licensed activities.67

Endnotes

1 The Singapore Government announced in 2020 that the Casino Regulatory Authority of Singapore will be regulated by a new generalist gaming agency, the Gambling Regulatory Authority. See ‘Establishment of Gambling Regulatory Authority and Review of Gambling Laws’, Ministry of Home Affairs (Web Page, 3 April 2020) < >.

2 Casino Control Act, NJ Stat Ann §§ 5:12-63(1), 5:12-69 (2021).

3 ‘Division of Gaming Enforcement’, State of New Jersey Department of Law & Public Safety (Web Page) < >.

4 Casino Control Act, NJ Stat Ann § 5:12-76a (2021).

5 Casino Control Act, NJ Stat Ann § 5:12-76k (2021).

6 Exhibit RC1618 Article: The Legalization and Control of Casino Gambling, 1980, 247 (n 14), 278 (n 174), 285.

7 Melissa Rorie, ‘Regulation of the Gaming Industry across Time and Place’ (Research Paper, Center for Crime and Justice Policy, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, September 2017) 2.

8 Bergin Inquiry Transcript (Cabot), 25 February 2020, 115.

9 Melissa Rorie, ‘Regulation of the Gaming Industry Across Time and Place’ (Research Paper, Center for Crime and Justice Policy, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, September 2017) 3.

10 Jennifer Roberts, Brett Abarbanel and Bo Bernhard, ‘Practical Perspectives on Gambling Regulatory Processes for Study by Japan: Eliminating Organized Crime in Nevada Casinos’ (Research Report, International Gaming Institute, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 25 August 2017) 14–15.

11 ‘About Us’, Nevada Gaming Control Board (Web Page) < >. This includes gaming machines, casinos and other types of wagering: see, eg, Gaming Control Act, Nev Rev Stat § 462.130 (2021).

12 ‘About Us’, Nevada Gaming Control Board (Web Page) < >.

13 ‘Gaming Commission’, Nevada Gaming Control Board (Web Page) < >.

14 Gambling Act 2003 (NZ) s 224.

15 Gambling Act 2003 (NZ) s 224. Section 10 of the Gambling Act 2003 (NZ) prohibits the licensing of any new casino venues.

16 Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act, RSA 2000, c G-1, s 3.

17 Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act, RSA 2000, c G-1, s 103(1).

18 Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act, RSA 2000, c G-1, ss 103(1), (3).

19 Casino Control Act, NJ Stat Ann § 5:12-79 (2021).

20 Gambling Act 2003 (NZ) s 333(1). This power is similar to the power conferred by s 10.4.10(1) of the Gambling Regulation Act 2003 (Vic).

21 Casino Control Act, NJ Stat Ann § 5:12-78 (2021).

22 Casino Control Act (Singapore, cap 33A, 2007 rev ed) s 54(1).

23 Gambling Act 2005 (UK) ss 119(1), 120(1)(c).

24 ‘Investigations and Enforcement Bureau’, MGC (Web Page) < >.

25 Mass Gen Laws ch 22C §70, ch 23K § 6(c) (2020).

26 ‘2018 Community Mitigation Fund Specific Impact Grant Application’, MGC (29 January 2018) < >.

27 Memorandum of Understanding by and between the MGC and the Massachusetts Department of State Police, dated 5 March 2014, cls 1–5 < >.

28 Memorandum of Understanding by and between the MGC and the Massachusetts Department of State Police, dated 5 March 2014, cls 8c, 12 < >.

29 Mass Gen Laws ch 23K § 4(20) (2020).

30 The website of the New Jersey State Police states that members of the Casino Investigations Unit (a division of the Casino Gaming Bureau) work in conjunction with the investigators from the Division. See ‘Casino Investigations Unit’, New Jersey State Police (Web Page) < >.

31 ‘Casino Investigations Unit’, New Jersey State Police (Web Page) < >.

32 AGLC, Casino Terms & Conditions and Operating Guidelines (22 June 2021) ss 4.11.2–4.11.3.

33 31 CFR §§ 1021.200–1021.210, 1021.320, 1021.400–1021.410, 1021.500–1021.540 (2021).

34 Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, RSC 2000, c 17; AGLC, Casino Terms & Conditions and Operating Guidelines (22 June 2021) s 18.2.1.

35 AGLC, Casino Terms & Conditions and Operating Guidelines (22 June 2021) ss 18.4.3–18.4.4, 18.4.8–18.4.9, 18.4.12, 18.5, 18.7–18.8.

36 Bergin Inquiry Transcript (Bromberg), 24 February 2020, 97.

37 Casino Control Act, NJ Stat Ann §§ 5:12-92a(3), c(4) (2021).

38 Casino Control Act, NJ Stat Ann § 5:12-92c(4) (2021).

39 Casino Control Act, NJ Stat Ann § 5:12-102g (2021).

40 Casino Control Act (Singapore, cap 33A, 2007 rev ed) s 110A.

41 Singapore, Parliamentary Debates, Legislature, 13 February 2006, 2323 (Mr Wong Kan Seng).

42 Casino Control Act (Singapore, cap 33A, 2007 rev ed) s 110B(2); Casino Control (Casino Marketing Arrangements) Regulations 2013 (Singapore) pt II.

43 Casino Control (Casino Marketing Arrangements) Regulations 2013 (Singapore) reg 13(1).

44 Casino Control (Casino Marketing Arrangements) Regulations 2013 (Singapore) reg 29.

45 Casino Control (Casino Marketing Arrangements) Regulations 2013 (Singapore) reg 7(1)(d)(i).

46 Regulations of the Nevada Gaming Commission and Nevada Gaming Control Board, current as of 21 August 2021, reg 25.020

47 Regulations of the Nevada Gaming Commission and Nevada Gaming Control Board, current as of 21 August 2021, reg 25.020

48 Bergin Inquiry Transcript (Cabot), 25 February 2020, 125–7.

49 See, eg, In the Matter of Wynn MA, LLC (MGC, 30 April 2019) 14; Bergin Inquiry Transcript (Rose), 25 February 2020, 170–1.

50 Jennifer Roberts, Brett Abarbanel and Bo Bernhard, ‘Practical Perspectives on Gambling Regulatory Processes for Study by Japan: Eliminating Organized Crime in Nevada Casinos’ (Research Report, International Gaming Institute, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 25 August 2017) 7–10.

51 Jennifer Roberts, Brett Abarbanel and Bo Bernhard, ‘Practical Perspectives on Gambling Regulatory Processes for Study by Japan: Eliminating Organized Crime in Nevada Casinos’ (Research Report, International Gaming Institute, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 25 August 2017) 10–11.

52 AGLC, Casino Terms & Conditions and Operating Guidelines (22 June 2021) s 4.9.10; Gaming Control Act, Nev Rev Stat § 463.170 (2021).

53 Bergin Inquiry Transcript (Rose), 25 February 2020, 175–6.

54 See discussion in In the Matter of Wynn MA, LLC (MGC, 30 April 2019) 14–16.

55 Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Regulation (Alta Reg 143/1996) s 20(1).

56 Jason Azmier and Robert Roach, ‘The Ethics of Charitable Gambling: A Survey’ (Research Report No 10, Canada West Foundation, December 2000) 3.

57 Casino Control Act (Singapore, cap 33A, 2007 rev ed) s 42(1).

58 Casino Control Act (Singapore, cap 33A, 2007 rev ed) s 42(1)(a)(i).

59 Casino Control Act (Singapore, cap 33A, 2007 rev ed) s 65(1)(b).

60 Casino Control Act (Singapore, cap 33A, 2007 rev ed) ss 66(1)(a)–(b), 66(3).

61 Singapore, Parliamentary Debates, Legislature, 13 February 2006, 2323 (Mr Wong Kan Seng).

62 Gaming Control Act, Nev Rev Stat § 463.0133 (2021).

63 Gambling Act 2003 (NZ) s 7.

64 AGLC, Casino Terms & Conditions and Operating Guidelines (22 June 2021) s 4.9.10.

65 AGLC, Casino Terms & Conditions and Operating Guidelines (22 June 2021) s 4.9.3.

66 Gambling Commission, Licensing, Compliance and Enforcement under the Gambling Act 2005: Policy Statement (June 2017) 8 [3.10].

67 Gambling Commission, Licensing, Compliance and Enforcement under the Gambling Act 2005: Policy Statement (June 2017) 8 [3.10].

Appendix K

Appendix K

Best practice in gambling regulation: international comparison tables

Table 1: Alberta, Canada

Regulator | Alberta Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Commission |

Overview of functions of the regulator | The functions of the AGLC under the Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act include to:

|

Obligations to cooperate with the regulator | Licensees and gaming employees must cooperate fully with AGLC inspectors and police officers attending at a casino. Licensees must, on the request of an inspector or the AGLC:

|

Statutory obligations relating to AML | Licensees must implement certain procedures if money laundering occurs or is suspected to have occurred. Specific AML requirements apply, including employee training and certification, verification of patron identity and reporting of certain transactions. |

Key persons subject to regulatory oversight | Key persons subject to oversight include:

|

Applicable tests or standards relating to key persons | The AGLC may terminate or refuse to issue a casino licence if satisfied that any of the applicant’s key employees, associates or connected entities:

|

Table 2: Massachusetts, United States of America

Regulator | Massachusetts Gaming Commission |

Overview of functions of the regulator | The functions of the MGC under the Massachusetts General Laws include to:

The Division of Gaming Enforcement supports MGC regulatory responsibilities by investigating and prosecuting allegations of criminal activity related to gaming establishments. The Division provides assistance to the MGC when considering gaming rules and regulations. The Investigations and Enforcement Bureau is the primary law enforcement agency for casino regulation. It investigates casino licensees and any activity taking place at a casino. |

Obligations to cooperate with the regulator | Licensees must cooperate with the MGC in all gaming-related or criminal investigations and must make readily available all documents, equipment and personnel requested during a gaming-related investigation. The Bureau may impose a civil administrative penalty for a failure to comply. |

Statutory obligations relating to AML | Casinos in Massachusetts have no express obligations in relation to money laundering under the Massachusetts General Laws. Casinos must comply with federal AML rules in the Code of Federal Regulations. |

Key persons subject to regulatory oversight | Key persons subject to oversight include:

|

Applicable tests or standards relating to key persons | When considering a licence application, the MGC must instruct the Bureau to investigate the suitability of all parties interested in the licence, including affiliates and close associates. Suitability involves consideration of overall reputation, integrity and character. |

Table 3: Nevada, United States of America

Regulators | Nevada Gaming Control Board and Nevada Gaming Commission |

Overview of functions of the regulators | The functions of the Gaming Control Board under the Gaming Control Act include to:

The Nevada Gaming Commission acts on Board recommendations and is the final authority on licensing matters. It may approve, revoke, suspend or apply conditions to licences. |

Obligations to cooperate with the regulators | There is no express requirement for licensees to cooperate with the regulators. The extent of cooperation appears relevant in determining penalties. Independent agents (junket operators) must agree to cooperate with all requests, inquiries and investigations of the Board or the Commission. |

Statutory obligations relating to AML | Casinos in Nevada have no express obligations in relation to AML under the Nevada Gaming Control Act. Casinos must comply with federal AML rules in the Code of Federal Regulations. |

Key persons subject to regulatory oversight | Key persons subject to oversight include:

|

Applicable tests or standards relating to key persons | The Commission may require an employee, agent, representative or lender of a licensee to apply for a licence where that person has power to exercise a significant influence over gaming operations. The Commission may also determine the suitability or require licensing of any person who provides services or property to a licensee. Suitability involves consideration of character, integrity, associations and criminal history. |

Table 4: New Jersey, United States of America

Regulator | New Jersey Casino Control Commission |

Overview of functions of the regulator | The functions of the NJCCC under the Casino Control Act include to:

The Division of Gaming Enforcement has general responsibility to implement the New Jersey Casino Control Act. It issues approvals, conducts audits and inspections of casinos, reports matters to the Commission and investigates violations of the New Jersey Casino Control Act. |

Obligations to cooperate with the regulator | Applicants and licensees must cooperate with the Division in the performance of its duties. There is a continuing duty to provide any assistance or information required, and to cooperate in any investigation or inspection, by the Division. Licensees also have a duty to inform the Division of potential violations of the New Jersey Casino Control Act. |

Statutory obligations relating to AML | Casinos in New Jersey have no express obligations in relation to AML under the New Jersey Casino Control Act. Casinos must comply with federal AML rules in the Code of Federal Regulations. |

Key persons subject to regulatory oversight | Key persons subject to oversight include:

|

Applicable tests or standards relating to key persons | The NJCCC cannot issue a casino licence unless it determines that all key persons meet the applicable qualification criteria. This involves consideration of the person’s character, honesty and criminal history, following which the NJCCC may issue a statement of compliance. |

Table 5: New Zealand

Regulator | Gambling Commission |

Overview of functions of the regulator | The functions of the Gambling Commission under the Gambling Act include to:

|

Obligations to cooperate with the regulator | There is no express requirement in the New Zealand Gambling Act that a casino operator must cooperate with the Gambling Commission. |

Statutory obligations relating to AML | There are no provisions in the Gambling Act that impose express obligations on a casino in relation to AML. Anti-money laundering is governed by the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter Financing of Terrorism Act 2009 (NZ). |

Key persons subject to regulatory oversight | Key persons subject to oversight are those who have a ‘significant influence’ in the casino. A person has a significant influence in a casino if the person:

|

Applicable tests or standards relating to key persons | To grant a casino operator licence, the Gambling Commission must be satisfied that persons with a significant influence are suitable, taking into account honesty, criminal history, financial position, business skills, any professional disciplinary action, and any other matter the Gambling Commission considers relevant. |

Table 6: Singapore

Regulator | Casino Regulatory Authority |

Overview of functions of the regulator | The functions of the CRA under the Casino Control Actinclude to:

|

Obligations to cooperate with the regulator | There is no express requirement in the Singapore Casino Control Act that a casino operator must cooperate with the CRA. |

Statutory obligations relating to AML | The casino operator must perform due diligence to detect or prevent money laundering and financing of terrorism in certain circumstances, including when opening patron accounts, for cash transactions over SGD10,000 and where there is a reasonable suspicion that a patron is engaged in money laundering or terrorism financing activity. The Casino Control (Prevention of Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing) Regulations 2009 (Singapore) also impose obligations relating to cash transactions, customer due diligence and record keeping. Casino operators must develop frameworks to prevent money laundering and terrorism financing, and to report suspicious transactions. |

Key persons subject to regulatory oversight | Key persons subject to oversight include ‘associates’ of a casino operator, being those who are or will be able to exercise a significant influence with respect to the management or operation of the casino. Assessing ‘significant influence’ involves consideration of the person’s position, financial interests, influence and powers in relation to the casino. |

Applicable tests or standards relating to key persons | To grant a casino operator licence, the CRA must be satisfied that each associate is a suitable person to be associated with the management and operation of a casino. This involves consideration of the associate’s reputation, integrity and financial resources. |

Table 7: United Kingdom

Regulator | Gambling Commission |